This dovetails on the article about the solar-powered airplane. While the efficiency of solar panels is critical to making them worth deploying as an alternative to fossil fuels, that’s only half the issue. The other half, of course, is price. Right now, the cost is a dollar a watt, which is pretty hefty. Fortunately, increasing efficiency and decreasing price go hand-in-hand. In an earlier article, we introduced the idea that adding wrinkles might make the cells more efficient, and therefore cheaper. This time, it’s a different method of increasing surface area: cones.

Of course, because these are really small cones, they are dubbed “nanocones,” and the Stanford University study was published in “Nano Letters.” There will come a point where we will have to stop using nano- to prefix to everything that’s in the nanometer range, since most technology already incorporates components in that range, and in the near future, all of it will. We’ll need to be a bit more specific. After all, we already have carbon nanocones, which are altogether different in application from these silicon cones. But that’s just a pet-peeve of mine – for now, nano’s captured everyone’s imagination, so I guess we’ll go with it everywhere we can.

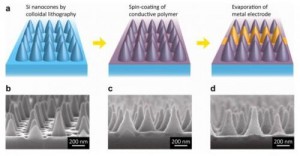

The key to the cost-savings of this design is the space between the cones. In a normal polymer cell, you need a full second layer for the polymer, but with this design, it can simply fill the gaps. Having a second layer involves using other materials, so this method renders those unnecessary.

If you’re thinking you’ve heard of cones being used to absorb light before, you’re not wrong. Of course, nature came up with this long ago, and the color-sensitive light receptors in our eyes are cone-shaped. It should come as no surprise that cones would be the most efficient shape for light absorption in photovoltaics as well, so why did researchers try out all sorts of other shapes, including nanowires and nanodomes? Just wanted to give all options a go, I guess. To be fair, nature doesn’t always do things efficiently. Consider the fact that our eyes are wired backward and upside down, requiring extra processing from our brains, for instance.

But, it looks like nature was right about the cones, at least (though maybe researchers will eventually find out that rods are better), and we are again one step closer to making solar power viable. Whatever the skepticism about solar power, there can be no doubt that, if we keep getting developments like these, the critics will eventually have nothing to say.